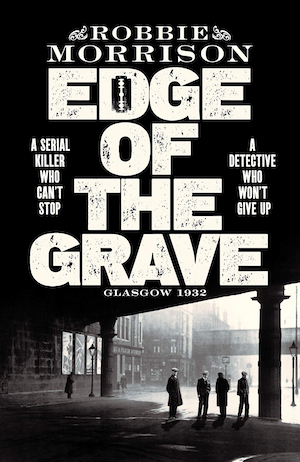

If you read comic books and graphic novels, the name Robbie Morrison might be familiar to you. Over the last 20 years, he has been prolific for 2000AD, writing stories for Judge Dredd, Shakara, Nikolai Dante and more. However, with the publication of Edge of the Grave, he is changing direction and joining a new clan – that of Tartan noir. Set in 1930s Glasgow, it’s about tough cops in a tough city during tough times. We pinned this novel as one of our most wanted crime books of 2021, so we decided to invite the author Robbie Morrison over for a virtual chat to find out more about the thinking behind it.

What will crime fiction lovers love about Edge of the Grave?

Edge of the Grave is the first book in a new historical crime series set in 1930s Glasgow, which Adrian McKinty has described as ‘Peaky Blinders meets William McIlvanney’.

It’s a gritty story that takes Detective Inspector Jimmy Dreghorn and his sergeant ‘Bonnie’ Archie McDaid from the flying fists and slashing blades of Glasgow’s gangland underworld to the backstabbing upper echelons of government and big business in the hunt for a twisted killer. Beyond the first book, the series will focus on the lives, loves and adventures of Dreghorn and McDaid, in what is planned to be a sweeping mix of crime thriller and family saga.

As an established writer of comics, what made you decide to write a crime novel?

It’s something I’ve wanted to do for even longer than I’ve been writing comics. It’s always good to challenge yourself and try something different, and, as much I like comics as a medium for storytelling, crime fiction has always been my real passion.

When I first started out, I was trying my hand at pretty much everything – radio plays, TV scripts, the first few chapters of a thankfully long-lost novel – but the first place to buy a story was Dundee publishers DC Thomson, for their Starblazers series of SF comic books. The lure of a cheque – albeit not exactly a large one – is hard to resist, so I concentrated my efforts on comics and was fortunate and privileged enough to build a decent career out of it. But then, after 20 years, you suddenly realise that there were also other things you always wanted to do – in my case, write a crime novel, or better yet, a whole series of them, hopefully.

What are the main differences between the two formats?

More words – LOTS more words! Comic scripts – similar in format to a screenplay or TV script – can be a little more conversational as they’re the springboard to the finished comic and are only seen by a handful of people; the finished product is the comic-book itself. So, I’d say the prose in a novel has to be tighter, because that is the finished product, however the basic principles of good storytelling are exactly the same. When the reader of a novel reaches the end of a chapter, you want them to be unable to stop themselves reading the next chapter, just like a comic reader reaching the cliff-hanger ending of an episode and being desperate to buy the next issue to find out what happens. The mediums might be different, but it’s all about the story ultimately.

Why did you choose the 1930s as your setting, and what research did you do?

I’ve had something of a fascination with the 1930s for as long as I can remember, stemming mainily from two sources. My family history, compiled into a handy volume a few years ago by my dad, which has connections to shipbuilding in Glasgow and along the River Clyde that stretch back four generations on both sides. And my love for the hardboiled crime fiction of that period, from Dashiell Hammett to Raymond Chandler, and the gangster films of James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart, whose sharp-suited, fast-talking protagonists also influenced the street gangs of the time.

Glasgow during the Great Depression, was a raucous, lawless city, with poverty, corruption, unemployment, extremist politics, sectarianism and the streets terrorised by razor gangs – the perfect location for a crime series!

Research was mainly reading, combined with walks around the city and a couple of visits to the Glasgow Police Museum in the Merchant City. Offhand, books that spring to mind are: Cloak Without Dagger, the autobiography of Percy Sillitoe, Chief Constable of Glasgow from 1931 to 1942; Growing Up in The Gorbals by Ralph Glasser; City of Gangs by Andrew Davies; and Molly Weir’s Shoes Were for Sunday and Best Foot Forward, inspired recommendations from my partner Deborah Tate.

How did you come up with James Dreghorn – what inspired him and the other characters?

Declaring war on the gangs in 1931, Glasgow controversially appointed Percy Sillitoe – an Englishman! – as the new Chief Constable. Sillitoe recruited the toughest officers in Scotland to form Britain’s first flying squad. Patrolling the streets in radio-cars, they were quickly nicknamed ‘the Untouchables’ by the press, after the elite unit put together in 1920s Chicago by FBI agent Eliot Ness to target the gangster Al Capone. The message is blunt: “The biggest gang in this city is the Glasgow Police.”

Our heroes, Inspector Jimmy Dreghorn and ‘Bonnie’ Archie McDaid are two of these tartan Untouchables. Dreghorn’s backstory is inspired by my grandfather, who worked in black squads in shipyards along the Clyde and boxed under the patronage of one of Scotland’s wealthiest landowners – elements that feature in the novel. Likewise, Archie McDaid is based upon a real policeman of the period; a larger-than-life bagpipe-playing Olympic wrestler and heavyweight boxing champion.

Other than Dreghorn, who was your favourite character and why?

I reckon it’s between: Bonnie Archie McDaid, a gentle giant in many ways, but also someone who likes to think all the problems of the world can be solved by a good, hard punch on the nose – and is happy to be the one to deliver it; and Ellen Duncan, a sharp-witted police constable who is determined to tear down barriers and become Glasgow’s first female plainclothes detective.

The theme of divisions comes across quite clearly – sectarianism, class, gender and so on. Tell us more about what you wanted to explore here?

I wanted to write a story that captured the power and drama of the era – crime, politics, wealth, poverty, attitudes, divisions, the spirit of the people and the spirit of the city and how they make each other what they are – but also hopefully have resonance to our world now. All the things you mention above are still as relevant now as they were in the 1930s, albeit in slightly different ways.

You’ve made Dreghorn quite progressive in his thinking, for example with regards to women in the police and some of the other divisions mentioned. Why did you choose to do this and is it realistic?

Dreghorn doesn’t really examine or intellectualise his attitudes or actions; it’s more of an instinctual thing, something he can’t stop himself from doing rather than something he feels he should be doing. My thinking was that his horrific experiences – a kill or be killed existence – on the battlefields of the Great War have made him step above petty prejudices such as gender, religion and class. He judges people individually, whether they’re deserving of his respect or not.

I may have taken a little artistic licence in the portrayal of WPC Ellen Duncan, as at this time, female officers weren’t allowed to make arrests or even leave the police station except to help out on ‘death calls’, informing people of a loved one’s death. However, by the 40s and 50s, there were women detectives in CID, so I reckoned I could legitimately make Ellen’s efforts to break through those barriers a part of the storyline. Dreghorn is one of the few to recognise and acknowledge her potential.

What kind of atmosphere were you hoping to generate in Edge of the Grave? With comics you have the artwork to rely on, so how did you meet the challenge?

I was aiming for verisimilitude, something that feels right rather than being 100% historically accurate; it’s my version of 1930s Glasgow after all, not a history book – although I hope it is very respectful to the reality of the city and the era. I wanted realism, but tinged with the mood of classic hardboiled crime fiction, film noir and gangster films, and shot through with that brand of humour that is both particularly Scottish and Glaswegian.

Obviously in comics, you have artwork to help generate mood, but when you’re writing a comics script – even though the style of writing might be more conversational – you’re still intent on firing the artist’s imagination with your descriptions of place, character and action. That, then, hopefully inspires the artist to bring something of themselves to the story.

When writing a novel, you’re still trying to get readers’ imaginations working, so that they visualise the characters, the places, etc. As a writer, the reader’s imagination is one of the most powerful tools you have. If you can spark that, then you can go anywhere.

Which other crime authors or books have inspired you, and why?

The work of the late, great William McIlvanney – Docherty, the Laidlaw novels – and the Tartan Noir school of crime-writing that he inspired is obviously a big influence; thrillers which mix fact and fiction, in the style of Philip Kerr and Robert Harris; that hardboiled crime fiction of the 30s and the classic film noir and gangster movies of the same period; novels which have crossover appeal beyond genres like Martin Cruz Smith’s Gorky Park and Don Winslow’s recent Cartel trilogy.

What’s next for you?

While I do have a graphic novel with Charlie Adlard – artist of The Walking Dead – in the pipeline, my main priority for the foreseeable future is the Dreghorn series and writing the follow-up to Edge Of The Grave.

Watch for our review of Edge of the Grave, coming soon.