Jeffrey McCall in PRAY AWAY. (Netflix)

At the start of Netflix’s Pray Away, a man approaches a group of strangers and tells them how he lived as a trans woman until, one day, he stumbled head first into Christianity

Now, Jeffrey McCall sees his past life as sinful. He lives as a cis man and is adamant that God saved him.

It’s a surprising start to a film that promises to dissect conversion therapy, but it was important to Pray Away director Kristine Stolakis that she include a representative of the movement in America today to show that the problem hasn’t gone away.

“My team, like myself, all have a personal connection to this issue,” Stolakis tells PinkNews. “My team is full of conversion therapy survivors, people that are queer who grew up in conservative or evangelical religious communities. We have really lived this issue in some way, and we all decided that capturing the fact that this movement continues is really important.”

Stolakis reached out to Jeffrey and asked if he would like to take part. She was “very forward” about the fact that Pray Away would include critical voices, she explains.

“I think that’s actually very important and ethical to do in a documentary. We did not pull the wool over his eyes at all. And to his credit, he agreed to be part of the film. So much of this world practices conversion therapy in private, in secret. There’s so much shame involved in all of this. The fact that he’s willing to go on the record is something I’m grateful for, even though we disagree about the consequences of his actions.”

Jeffrey’s experience is just one of the stories captured in Pray Away, the powerful new Netflix documentary that shines a light on conversion therapy – also dubbed the “ex-gay movement” – in America. Most of those interviewed are former conversion therapy leaders who subsequently left the movement. All, bar Jeffrey, regret their involvement in conversion therapy practices and each one now considers themselves a part of the LGBT+ community.

“I do think Jeffrey has good intentions and believes he’s doing the right thing,” Stolakis says. “I do not think this is a movement of a few bad apples. These are people who are often survivors of some kind of conversion therapy themselves, and we talk a lot in the edit about how this is really an example of internalised homophobia and transphobia wielded outwards.

“I know Jeffrey would never use those words to describe where he is – he truly believes he is no longer trans.”

Pray Away director was inspired to delve into conversion therapy by her uncle’s traumatic experience

Jeffrey’s story had a painful resonance for Stolakis. Her much-loved uncle had come out as a trans girl as a child, but as was common at the time, he had his identity crushed by adults who saw his gender as a threat and grew up to live life as a man.

“I knew him mostly as my babysitter growing up,” Stolakis says. “He was about 25 minutes away from me, and I spent most days with him after school. He was one of the first people that I loved who loved me.”

When Stolakis was growing up, her uncle experienced “incredible mental health challenges”, including depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, addiction and suicidal ideation.

“As I grew up, I learned that was the result of him going to conversion therapy and growing up in a transphobic culture that had taught him that being trans was both a sickness and a sin. This was a belief he was never able to shake for his whole life.”

Tragically, Stolakis’ uncle passed away just a couple of weeks before she went to film school. It was in that moment she decided her first feature film would be about America’s conversion therapy movement.

“I started doing research and what I found that really helped me understand my uncle and his depth of belief that change was possible is that the vast majority of conversion therapy organisations are actually run by LGBTQ individuals themselves who claim that they have changed, that they know how to change, and they are teaching others to do the same.”

This was a “lightbulb” movement for Stolakis, who was able to see for the first time that her uncle’s belief was not “some wacky, niche, out there thought”, but was something he picked up on from Christianity.

Through her research, Stolakis discovered that conversion therapy was still in full swing in America. She became more determined than ever to cast a critical eye on the harmful practice.

“It’s not a thing of the past,” she says. “We know in the US alone that nearly 700,000 people have gone through this, we know this continues on every major continent. This is a present tense issue, and I wanted our film to capture that. Pray Away is the result of that research. We really grounded this film in the undeniable pain and trauma that this movement causes.”

Pray Away explores the impact of trauma on the conversion therapy movement

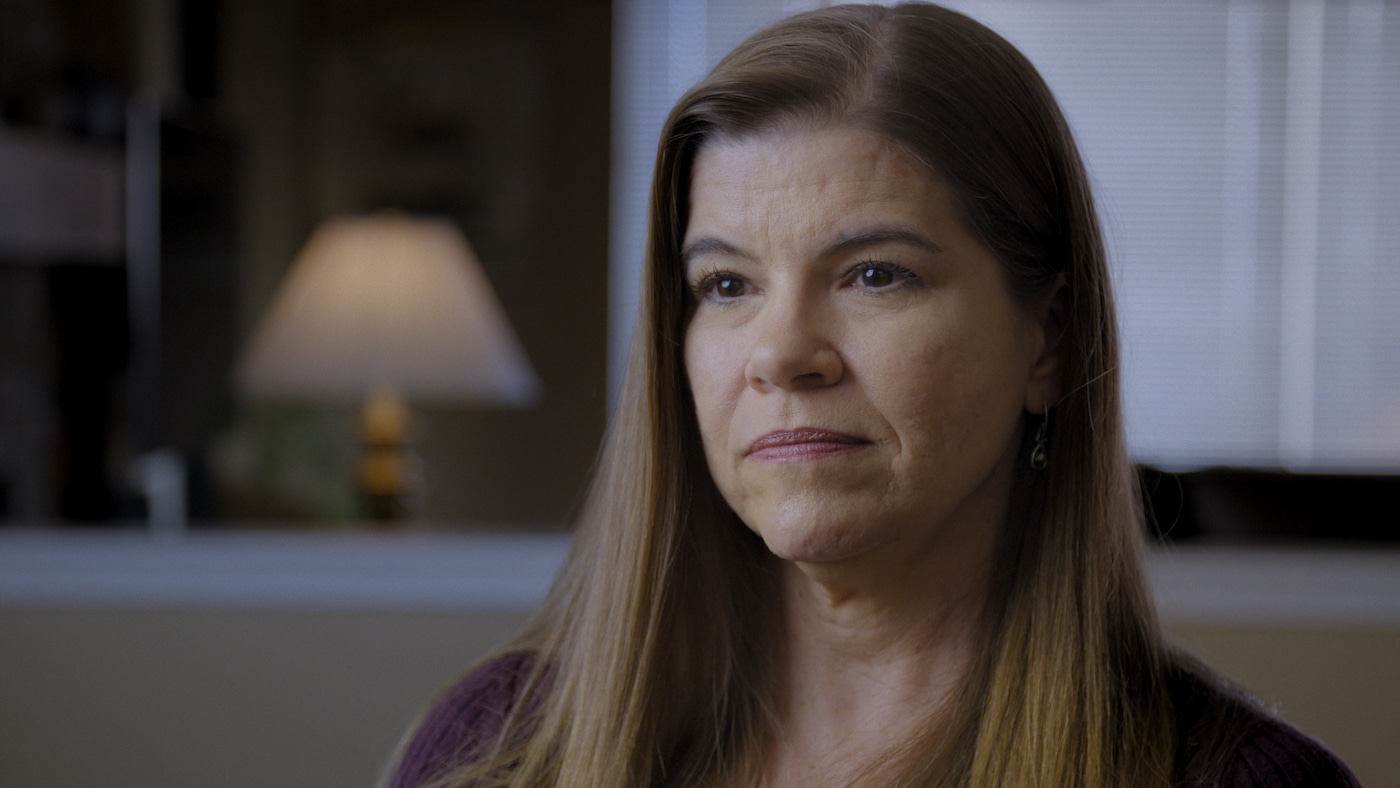

Through a series of interviews, Pray Away unpicks the traumas experienced by the former leaders of the ex-gay movement. At one point, Yvette Cantu Schneider recounts how she lost around 17 gay friends to AIDS as a young queer woman.

Shortly afterwards, she renounced her sexuality and her former life. In the years that followed, she became firmly embedded in the “ex-gay movement”, eventually ascending to a leading role with the Family Research Council in Washington DC.

“A lot of people who end up in leadership who are just zealously believing in the ex-LGBTQ movement more generally enter it from a place of trauma,” Stolakis says.

“I cannot tell you the number of people I saw at, for example, Freedom March rallies, who would talk about how they had been raped, molested, gone through a horrible break-up right before joining the movement. And, unfortunately, those are the reasons the conversion therapy movement claims, falsely, that people become LGBTQ.

“You would see people on stage saying, ‘I was molested as a child, that is why I’m a lesbian,’ and I would say, ‘Oh my gosh, that’s not why you’re a lesbian – that’s why you have trauma and you need real support and help with what I am sure has resulted in all sorts of mental health challenges, but you being LGBTQ has nothing to do with that.”

Many of the people Stolakis and her team interviewed in Pray Away sought conversion therapy as a direct result of their traumas.

“I think for people who transitioned into leadership, that experience of trauma often clouded their own connections,” Stolakis says.

“It made them very desperate for community and belonging, and that might sound like a trite analysis, but I think wanting community and belonging is one of the most human things we all go through, so the promise of that in the midst of the cloud of that trauma was so, and is so, potent.

“Trauma and mental health issues are such a part of the reason people are part of this movement,” Stolakis adds. “The problem is that people get taught their trauma and mental health issues are the result of being LGBTQ, and the message is, it’s a sickness and it’s a sin and you’ve got to try and change that – and that is not the case.

“People need real mental health support when they go through a trauma, being LGBTQ is not a problem. Our larger culture of homophobia and transphobia can cause people trauma, but sexual orientation or gender identity isn’t the source.”

Because she has seen firsthand the impact conversion therapy has had on victims, Stolakis felt “competing feelings” while speaking to the former leaders of the movement.

“I have to say, overwhelmingly what I felt when spending time with former leaders was sadness, not anger, because I saw them as a product of this larger culture of homophobia and transphobia,” Stolakis says.

“For me and my creative team, we didn’t want to edit a film that told people how to think about the individuals in our film, because it’s going to really depend on your own experience of this movement. I did not want to shove the expectation of either empathy or anger down the throats of our future viewers. I really wanted to let people feel what they’re going to feel, and it’s going to be complex and different for every person, and I’ve spoken to enough people to know it truly is different for every person.”

She continues: “We tried to capture the thing that we know undeniably is true, which is that no matter anyone’s intention, this movement causes pain and trauma – period. That is the reality. There are no two sides to this. That is just the reality.”

Kristine Stolakis wants to see conversion therapy banned in all settings

Over the course of its 100-minute running time, Pray Away charts how the conversion therapy movement started to fracture following the passage of Prop 8, a law that banned same-sex marriage in California in 2008. That was the moment, Stolakis says, that the denial of some leaders finally broke.

“Denial is a huge part of the reason leaders continue to do the work they do,” Stolakis says. “If you truly believe you’re helping people and that God is directing you, and you have that internalised homophobia and transphobia in there as well, it is just a recipe for denial.

“For a lot of these leaders, what we track in the film is the way in which their denial breaks. And for a couple of leaders in our film, Prop 8, the passage of Prop 8, was a sobering moment. It was a time when people realised their actions had not only taken away people’s rights, but had truly taken away their dignity as humans. That was a touchstone of when people started to change their minds about what they were doing.”

While the movement started to fracture, leading to the dissolution of one of America’s biggest conversion therapy organisations, the practice is still common today. Stolakis hopes Pray Away will shine a light on the need for extensive conversion therapy bans to be put in place across the world.

“In the US specifically, when you see that a ban has passed against conversion therapy, that only bans licensed therapists generally who are practicing with minors,” she explains. “We have really robust religious freedom protections that do exempt religious organisations and practices, and that is a problem.

“We know that conversion therapy happens the most in religious organisations with a pastor acting as a pseudo-counsellor, in a Bible study that looks like a peer-support group where this idea that being LGBTQ is a sickness or a sin is promoted and passed around. If conversion therapy doesn’t stop there, it’s not going to stop.”

Stolakis is frustrated when she sees countries like the UK debating whether religious organisations should be allowed to continue practicing conversion therapy. The concept is “out of touch with the reality” of what conversion therapy looks like, she explains.

“If you want to end this, it has to end in all places, and that includes in religious organisations. I do not think this is a religious freedom issue – I think that is a complete mischaracterisation of what the essence of this issue is. This is a mental health issue, this is a child abuse issue. This is not something we have to fight about politically. I think we can all agree that abuse is a problem and we need to end it. So I hope our film and our partnership with Netflix helps start an international dialogue about ending this in all forms and in all spaces.”

Pray Away is released on Netflix on Tuesday (3 August).