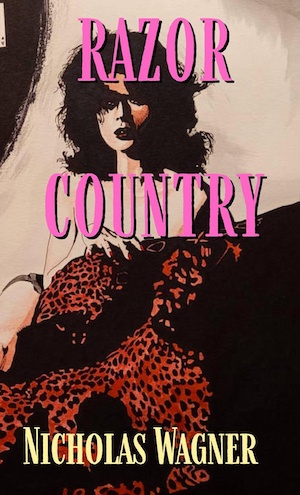

Sometimes, a book takes you by surprise. In an age where cosy crime is having a resurgence and shop shelves creak with hybrid novels more romance than thriller, Razor Country comes along and punches you in the gut. This hardboiled collection of tales by author Nicholas Wagner reminds us why we’ve always loved short, punchy, pulp fiction.

Razor Country is a novella in 21 parts, each a short story about private investigator Colm Steiner. He works for an Enquiry Service in the years before and after World War I. Steiner is a laconic, hard-drinking ex-soldier with an innate desire to do the right thing, but more than ready to shoot first and ask questions later if it gets the job done.

Each chapter reads like a standalone adventure, told in a rapid-fire, matter-of-fact style. Our protagonist is dispatched on a variety of missions around the British Empire and North America, often to locate missing people or resolve local disputes. Sometimes, these involve working with shady mobster types willing to pay for extra muscle. Sometimes, Steiner, finding himself with downtime between jobs and nothing to do but drink and pay for sex, will indulge his natural curiosity or come to the aid of friends. A few of the characters pop up repeatedly, but for the most part, there is no causal connection between the mysteries, and Steiner experiences little character development – unless recognising his own booze problem counts.

It’s derivative, certainly, but fun and written with a captivating prose style. What keeps the pages turning are the energetic, vivid descriptions, the distinctive dialogue and the brutal characters who are brought to life in just a few lines before they vanish or die. It’s pure, 20th-century dime-novel stuff, and it’s a delight.

This is Dashiell Hammett territory. Although told in the third person, it has shades of the Continental Op stories. Fans of Lee Child’s Jack Reacher or TV’s The Equalizer franchise will also enjoy a sense of familiarity.

Wagner excels at creating atmospheric settings, both rural and urban. From London to Quebec via the battlefields of France – “His term in the trenches was brief and compared unfavorably with his days in Africa” – Steiner’s adventures take us to lawless places, which are described with charm. The author drops in enough detail – from sheep shearing competitions to union meetings – to make the world feel real.

The period is undoubtedly crucial to the book’s personality. The Edwardian and Interbellum settings mean long horse rides, Model T Fords and steam trains. But this is no Poirot. It’s a time of transition, and there’s a sense on every page that the authorities have little power or inclination to fix the world’s problems. Steiner and his associates are cynical and pragmatic, just happy to find a tavern to drink in and prepared to put a bullet in somebody if an argument grows heated.

If the descriptions of each location are lush, the language used for the action scenes is plain, like a police case file. Gunfights are described prosaically as though shooting somebody and then going to bed is the obvious thing to do after a shot of gin. “The man grabbed a surgical knife from the shelf, and Colm shot him in the stomach. The man slumped to his knees and stared at the gushing wound. Colm tied both of the men up with rope, found a telephone and dialed the local constable.” It’s fast and compulsive: a news report from a bygone world.

Like the best hard-boiled gumshoe fiction, the dialogue can be pacey and reliant on slang, but it’s often a little forced, somewhat overly-mannered, as befits the era.

“Have you entered our establishment with a pure heart and purity of intent?”

“I’ve done my best to hollow out my worst instincts.”

“What more can be asked of a man?”

It can feel a little try-hard, but not a word is wasted. Steiner reaches conclusions quickly and the reader often has to catch up based on a few musings.

He’s a character alienated from society, a society which is itself corrupt and broken. The ambience harks back to the final days of the Wild West, particularly in early scenes set in the Australian Outback, evoking a similar vibe to that found in Richard Matheson’s Journal of the Gun Years. There are shades of both cowboy and, in later Prohibition Era episodes, gangster fiction here.

Occasionally, the stories veer towards the Gothic, bringing to mind Edgar Allen Poe. In one mystery, Steiner has to search a crumbling Moldovan mansion in the company of the Countess Moruzi, who has filthy hair and “the gleaming eyes of a mystic”. In another, a rivalry between two London street puppeteers leaves one of them hanging from the rafters like a marionette. Creepy. Surprises like this prevent the novella from becoming clichéd.

The final tale is short and concludes abruptly in a way that offers little comfort. You know it won’t end well for this hard-living, uncompromising man, and you’re sure it shouldn’t, but Razor Country is almost over too soon.

Author Nicholas Wagner is a writer and independent filmmaker from Virginia. He’s penned several crime novellas, but no prior reading is necessary to dive in here. If you’re tired of world-weary protagonists solving morally ambiguous problems with their pistols, then this isn’t for you. But for the rest of us, it’s an entertaining, if old-fashioned, collection of curious tales.

Self-published

Print/Kindle

£0.78

CFL Rating: 4 Stars