A queer academic and secret witch, Jamie is gearing up to start a dissertation on Emily, a fictional 18th-century novel that may have been written by Tom Jones author Henry Fielding’s brilliant sister Sarah or her lifelong companion, Jane Collier. But after Jamie teaches her grieving mother how to cast spells, things get dangerous fast. Charlie Jane Anders’ Lessons in Magic and Disaster tracks Jamie’s scholarly endeavors and magic teaching-gone-wrong as they intersect in surprising ways, eventually revealing centuries-old secrets and unearthing generational trauma.

Jamie’s research process, although aided by magic, will definitely strike a chord for anyone who has spent hours in an archive. What was your research process like for this book?

I thought I knew a lot about 18th-century literature! How little I actually knew.

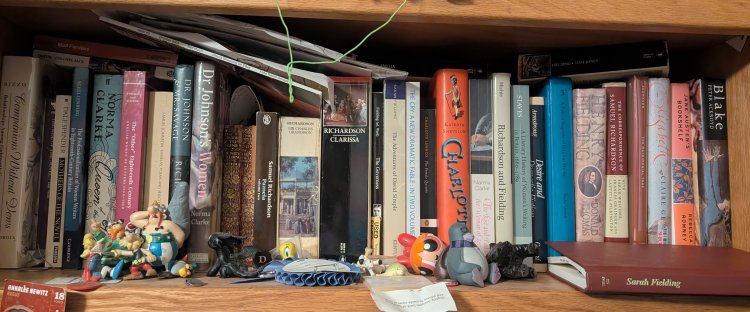

Basically, I started chasing stray references here and there, and it led to amassing a giant stack of scholarly books as well as primary texts. I kind of went overboard, honestly. I’m attaching a photo of my 18th-century shelf so you can see for yourself.

I read as much literature from the time as I could, especially the works of Sarah Fielding and Jane Collier, plus biographies of larger-than-life figures like Charlotte Charke, Laetitia Pilkington and Elizabeth Chudleigh. I found the free audiobooks at LibriVox utterly invaluable, allowing me to listen to talented volunteers reading 18th-century novels as I was taking long walks.

I interviewed a handful of scholars over Zoom and started to get an idea of exactly how these colorful women and queer people were coping with an era that was becoming more and more repressive. (Long story short—after the Stuart Restoration in 1660, there was a period of liberalization where women could live however they wanted, but then around 1730, things started to get more restrictive again.)

At one point, I got COVID and decided to do nothing but lie around reading until I was testing negative, which meant I spent a few weeks just reading scholarly texts. I got utterly sucked into reading books like Companions Without Vows by Betty Rizzo, which is full of scandalous and bizarre details about women of the era. I basically inhaled every book I could get my hands on.

How much of the history that Jamie studies is real?

Most of it! I’ll start by telling you what I made up and then get to the true stuff. (I’m just so excited that you’re asking me about this, I am dancing in my chair.)

Basically, I invented a fake 18th-century novel called Emily from whole cloth. It’s similar in some ways to real novels from the time, especially the “moral romance” genre, where decent people try to remain good in a messed-up world. (Back then, romance just meant “novel” or “story.”) I ended up writing large chunks of Emily, along with letters and other documents surrounding it. Sadly, no correspondence between Sarah Fielding and Jane Collier survives, so I had to invent some as well. There’s also no proof that Sarah Fielding ever met Charlotte Charke [an actor whom Jamie theorizes may have inspired part of Emily]—but she easily could have, since Charlotte worked for Sarah’s brother Henry.

When I went to college, I was taught that Henry Fielding was one of the few Georgian authors who mattered—all of them men. But in fact, Sarah Fielding was also a bestselling, influential author and critic, and she helped expand our idea of what the English novel could be. Sarah Fielding wrote the first novel for children and teens, The Governess. She also co-authored a fascinating experimental novel (which is pretty metafictional) called The Cry, with her best friend, Jane Collier. Jane Collier, meanwhile, wrote a satire about cruelty that hits as hard as anything Henry ever wrote, called An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting. Sarah and Jane were lifelong friends and lived together for some years, until Jane died.

Also, Sarah and Jane were on the fringes of the Blue Stockings circle as well as a group of women who were trying to found a female-only community near Bath. I feel like it’s very possible that Sarah and Jane were lesbians, along with other women in that group. I started to see Sarah, Jane and Charlotte as part of a queer subculture in Georgian England, which resonates a lot with the fight for queer liberation that Jamie and her family are part of.

“I really wanted the magic to be lonely, for lack of a better word.”

Can you talk a little about the real Charlotte Charke? What drew you to including Charke’s story?

OMG this is my favorite interview in forever. Thank you for asking about Charlotte!

Charlotte Charke was the daughter of Colley Cibber, an actor and playwright who became the poet laureate of the United Kingdom in 1730. From an early age, Charlotte dressed herself in her father’s clothes, and when she started her own career in the theater, she generally played “breeches parts”—meaning that she dressed as a man and often played parts written for men. Colley was known for playing a character named Lord Foppington, an over-the-top, ridiculous dandy with a giant wig, and Charlotte took this parody even further. When satirist and gadfly Henry Fielding wrote a play making fun of Colley in 1736, Charlotte played the role of her father—which resulted in Colley disowning her and cutting off her inheritance. When the theaters were closed in 1737, Charlotte lived and worked as a man, doing men’s traditional jobs as well as running a puppet theater and traveling the country as a strolling player. Charlotte even took a wife, about whom we know almost nothing.

So basically . . . Charlotte Charke is a queer icon.

I knew little about Charlotte Charke until pretty recently, despite being obsessed with 18th-century literature and Henry Fielding in particular. (I’m using she/her pronouns for Charlotte, because that’s what she used when she was alive.) When I started working on Lessons in Magic and Disaster, I decided my main character would be a scholar studying 18th-century literature, and this led to me discovering so many fascinating people whom I’d never learned about in my college lit classes. Charlotte Charke stood out, burned brighter and demanded to be included in my story. The 18th-century stuff in my book grew and grew, until it became a huge part of the story, with Charlotte at the center.

The epigraphs for each chapter bring one more level of depth to Lessons in Magic and Disaster. Are they all from real sources? Where and how did you find them?

Oh man. First of all, thanks for the compliment!

Most of the epigraphs are fake—I wrote them myself, along with the other 18th-century excerpts. (I had a dozen tabs open on my browser, including Samuel Johnson’s original dictionary and the Project Gutenberg pages for a bunch of contemporary works, so I could make sure I was using words the way people would have used them back then.) I tried to come up with pithy quotes from my fictional novel that went with whatever was going on in the story at the time.

But I did use some real stuff, like that amazing quote from Fanny Burney: “Nothing is so delicate as the reputation of a woman.” And some quotes from Laetitia Pilkington and Charlotte Charke that felt appropriate. Plus, for the chapters retelling Serena’s past, I hunted down quotes from the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s that helped illuminate the world she was living in at the time. But most of the epigraphs are me inventing chunks of Emily.

Every magic system, however loose, seems to have its necessary components, and for Lessons in Magic and Disaster, that necessary component is the liminal space between decay and human construction. Why did you choose to focus on these spaces?

Honestly, it just felt right. When I started working out the magic in the book, I didn’t want anything too mechanistic or rules-based, and I really wanted the magic to be lonely, for lack of a better word. I wanted Jamie to be someone who had been very isolated, whose isolation had led to her discovering that if she went into places that people had abandoned, she could make something happen.

To do magic in this world, you need to find a spot on the edge of nature where people built something that is now crumbling and being reclaimed by nature. This also plays into a few of my obsessions, like boundaries—see day and night in The City in the Middle of the Night—and the relationship between humans and nature, which is a huge part of All the Birds in the Sky.

I’ve heard it argued that stories about witches—especially stories where witchcraft is hidden—are inherently queer. How much do you think this is true about your relationship with the literary witch?

I hadn’t heard this before, but I think it makes rather a lot of sense. Witches tend to be a bit disreputable and to be outcasts whom people both need and hold at a remove. Often, witches have an aspect of gender-nonconformity. Some of my favorite witch stories involve transgressive sex or naked rituals, too. And when I think about my favorite recent witch stories, they include things like The Sapling Cage by Margaret Killjoy or The Story of the Hundred Promises by Neil Cochrane, which definitely bring the queer elements to the fore.

Read our review of ‘Lessons in Magic and Disaster’ by Charlie Jane Anders.

As Jamie’s spouse, Ro, points out, any work of magic that acts on a person other than the caster could be seen as a violation of that person’s autonomy. Do you think there’s something inherently controlling about wanting to do magic?

I think that the question of consent is something that ought to be a part of any story about power and the ability to make changes in someone’s life. Ro is absolutely right that no matter how benevolent your intentions are, even if you’re only trying to bless someone else, you’re exerting power over them, and it’s kind of messed up to do that without their permission. One of the things I loved about writing Ro is that they think very deeply about ethics and being a good person, and their voice became more and more important as I worked on the book.

There’s something that Jamie realizes toward the end of the book: that trapping someone else inside your story is a form of forced imprisonment, and that’s a decent way of thinking about magic overall.

So much of this novel is about intergenerational trauma and the relationships between mothers and daughters. Are there any particular narratives (fiction or nonfiction) that shaped how you approached these topics?

Yes! I was working on a list recently, but off the top of my head . . . both of Megan Giddings’ recent books have fascinating mother-daughter relationships. (And her book The Women Could Fly is one of my favorite witch books.) Rouge by Mona Awad is an utterly devastating story about a mother-daughter relationship that is full of hurt, but ultimately reveals a tenderness that knocked me sideways. Wake the Wild Creatures by Nova Ren Suma is a must-read story for anybody who likes damaged mothers and their fierce daughters. Honestly, we are blessed with some amazing stories about how mothers pass their trauma as well as their power down to their daughters.

Some of our readers might not know that in addition to being a fantastic speculative fiction writer, you’re also one of the former editors of io9, a podcaster and a nonfiction writer. How do these different kinds of interacting with story and media intersect with your fiction writing?

I feel like it’s all helpful, because all of these facets of my life involve thinking about stories in different ways. I love geeking out about writing, something I started doing at io9 and eventually turned into a book called Never Say You Can’t Survive. My favorite moments in recording Our Opinions Are Correct are the ones where we stumble across a new and fascinating way to think about stories. It’s always a good day when a conversation about speculative fiction leads to a lightbulb moment that leaves me fired up and excited to write more stories.

Author photo of Charlie Jane Anders by Annalee Newitz.