When most people think of Shirley Jackson, they think of horror. The Haunting of Hill House is often cited as the archetypal 20th-century ghost story. Even scaremonger-in-chief Stephen King regards Shirley Jackson as a major influence, devoting 30 pages of his 1982 memoir Danse Macabre to her work.

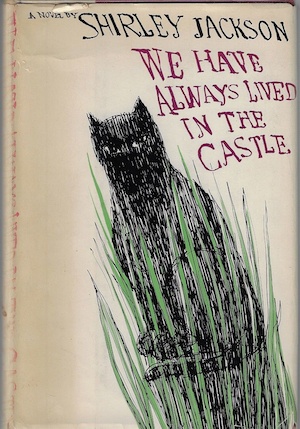

The Californian writer is justifiably famous for her stories of the supernatural and macabre. But it’s not the complete picture, and I have a soft spot – indeed, huge admiration – for her 1962 masterpiece, We Have Always Lived in the Castle. In this slice of Americana she demonstrates how well she also understood the thrilling potential of the crime genre.

Novelist Jonathan Lethem reminds us that Jackson’s influential supernatural yarns are only a fraction of her talent. Writing in his 2006 introduction to We Have Always Lived in the Castle, he says, “She’s both perpetually underrated and persistently mischaracterised as a writer of upscale horror, when in truth a slim minority of her works had any element of the supernatural (Henry James wrote more ghost stories).”

It’s her final book and tells of two sisters living an isolated life following a family catastrophe. She penned it while enduring chronic ill health, including conditions brought about by her smoking and addiction to prescription medications. She also had anxiety issues, like agoraphobia.

The latter manifests very clearly in the novel. It’s set in a bigoted New England town that’s fictional but reminiscent of the Vermont village where the author lived later in life. She hated it, and that distaste spills over into her descriptions of the uptight settlement – there is an air of ignorant menace about life beyond the fences of our heroine’s home. Key moments in the book touch on social commentary, highlighting small-town prejudice and how people can turn on those perceived as different or ‘other’.

Dead to begin with

It’s a murder mystery of sorts, but the deaths occurred before the book starts. When we first encounter the novel’s narrator, Mary Katherine ‘Merricat’ Blackwood, her sister Constance and disabled Uncle Julian, they live in the aftermath, secluded and shunned. They hide in the family mansion, a short walk from the town. On this estate, six years earlier, the family’s dinner was poisoned, and four people died, including the sisters’ parents. As Merricat explains in the energetic opening paragraph of the novel, “Everyone else in my family is dead.”

The police nabbed Constance for the poisoning, but she was acquitted. This hasn’t stopped the townsfolk from vilifying the Blackwood sisters. Sweet-natured Constance is still the prime suspect in their eyes, and she has developed agoraphobia because of the stress. The sisters are devoted to each other and their uncle’s care, enjoying the serenity of their private grounds. Merricat fears any change to this peaceful status quo, so she’s frustrated and angry when cousin Charles shows up and starts clumsily trying to charm his way into their lives.

There are hints of crime in the main narrative – Charles is clearly trying to weasel his way into their money – but it’s the mysterious murders of the Blackwood clan which hang like a fog over everything.

There is some light detective work at play: Constance figured out who killed the family, although she keeps it to herself, while Merricat is the only one who sees Charles’ true motives. The joy of the book isn’t in finding out what happened (although it is delightfully teased) but in the suspense surrounding the few characters in this pressure-cooker setting. The dialogue is clever and emotional, revealing just the right amount of character. It is often witty but layered with melodrama as though it belongs in a black-and-white film noir.

The book doesn’t confirm whodunnit until page 110, and the revelation will be no surprise to any reader who has followed Merricat’s uncompromising, somewhat unhinged thought processes from the beginning. “I am going to put death in all their food and watch them die.”

Alone together

Merricat is an unreliable, dangerous narrator. Still, we nonetheless side with her because of her youthful energy and candour and because the outside world undoubtedly is awful. She is a defender; her obsession with folk magic, charms and curses is aimed at protecting the childhood home from outside influence. The remote setting and Merricat’s little rituals convey a sense of oddness despite the trio going about everyday things, like baking or reading library books.

The haunting ending sees Uncle Julian die too, and the two sisters retreat even further into themselves. They occupy the dilapidated house, which has come to look like a castle following the loss of its roof in a fire – as nature grows around the ruins, Merricat and Constance’s isolation is assured. It’s as though they’ve been exiled by way of punishment, but the joke is on the rest of civilisation because they prefer it. The last line of the book is one of triumph: “We are so happy.”

There’s a feminist streak to this tale of sisterly love. It’s a story of two outcast women who don’t tolerate the impositions of a male-dominated society. Writing in The Guardian in 2016, Chocolat author Joanne Harris revealed herself as a fervent admirer of Shirley Jackson, writing that Jackson’s work captures the hidden rage of women and their struggle for agency in the world.

What I love about this book is that, told by another author, this plot might have been a classic cosy crime – a poisoning at a dinner in a posh stately home. But it comes at you disguised as a spooky tale of obsession, dripping with hints of American witchcraft. It feels both classic and powerfully modern at the same time, a murder story told with wit and pace by a virtuoso of the Gothic horror genre.